NEET MDS Lessons

Orthodontics

SEQUENCE OF ERUPTION OF DECIDUOUS TEETH

Upper/Lower A B D C E

SEQUENCE OF ERUPTION OF PERMAMENT TEETH

Upper: 6 1 2 4 3 5 7 Lower: 6 1 2 3 4 5 7

or 6 1 2 4 5 3 7 or 6 1 2 4 3 5 7

ANTHROPOID SPACE / PRIMATE SPACE / SIMIEN’S SPACE

The space mesial to upper deciduous canine and distal to lower deciduous canine is characteristically found in primates and hence it is called primate space.

INCISOR LIABILITY

When the permanent central incisor erupt, these teeth use up specially all the spaces found in the normal dentition. With the eruption of permanent lateral incisor the space situation becomes tight. In the maxillary arch it is just enough to accommodate but in mandibular arch there is an average 1.6 mm less space available. This difference between the space present and space required is known as incisor liability.

These conditions overcome by;

1. This is a transient condition and extra space comes from slight increase in arch width.

2. Slight labial positioning of central and lateral incisor.

3. Distal shift of permanent canine.

LEE WAY SPACE (OF NANCE)

The combined mesiodistal width of the permanent canines and pre molars is usually less that of the deciduous canines and molars. This space is

called leeway space of Nance.

Measurement of lee way space:

Is greater in the mandibular arch than in the maxillary arch It is about 1.8mm [0.9mm on each side of the arch] in the maxillary arch.

And about 3.4mm [1.7 mm on side of the arch] in the mandibular arch.

Importance:

This lee way space allows the mesial movement of lower molar there by correcting flush terminal plane.

LWS can be measure with the help of cephalometry.

FLUSH TERMINAL PLANE (TERMINAL PLANE RELATIONSHIP)

Mandibular 2nd deciduous molar is usually wider mesio-distally then the maxillary 2nd deciduous molar. This leads to the development of flush terminal plane which falls along the distal surface of upper and lower 2nd deciduous molar. This develops into class I molar relationship.

Distal step relationship leads to class 2 relationship.

Mesial step relationship mostly leads to class 3 relationship.

FEATURE OF IDEAL OCCLUSION IN PRIMARY DENTITION

1. Spacing of anterior teeth.

2. Primate space is present.

3. Flush terminal plane is found.

4. Almost vertical inclination of anterior teeth.

5. Overbite and overjet varies.

UGLY DUCKLING STAGE

Definition:

Stage of a transient or self correcting malocclusion is seen sometimes is called ugly duck ling stage.

Occurring site: Maxillary incisor region

Occuring age: 8-9 years of age.

This situation is seen during the eruption of the permanent canines. As the developing p.c. they displace the roots of lateral incisor mesially this results is transmitting of the force on to the roots of the central incisors which also gets displaced mesially. A resultant distal divergence of the crowns of the two central incisors causes midline spacing.

This portion of teeth at this stage is compared to that of ugly walk of the duckling and hence it is called Ugly Duckling Stage.

Described by Broad bent. In this stage children tend to look ugly. Parents are often apprehensive during this stage and consult the dentist.

Corrects by itself, when canines erupt and the pressure is transferred from the roots to the coronal area of the incisor.

IMPORTANCE OF 1ST MOLAR

1. It is the key tooth to occlusion.

2. Angle’s classification is based on this tooth.

3. It is the tooth of choice for anchorage.

4. Supports occlusion in a vertical direction.

5. Loss of this tooth leads to migration of other tooth.

6. Helps in opening the bite.

Edgewise Technique

- The Edgewise Technique is based on the use of brackets that have a slot (or edge) into which an archwire is placed. This design allows for precise control of tooth movement in multiple dimensions (buccal-lingual, mesial-distal, and vertical).

-

Mechanics:

- The technique utilizes a combination of archwires, brackets, and ligatures to apply forces to the teeth. The archwire is engaged in the bracket slots, and adjustments to the wire can be made to achieve desired tooth movements.

Components of the Edgewise Technique

-

Brackets:

- Edgewise Brackets: These brackets have a vertical slot that allows the archwire to be positioned at different angles, providing control over the movement of the teeth. They can be made of metal or ceramic materials.

- Slot Size: Common slot sizes include 0.022 inches and 0.018 inches, with the choice depending on the specific treatment goals.

-

Archwires:

- Archwires are made from various materials (stainless steel, nickel-titanium, etc.) and come in different shapes and sizes. They provide the primary force for tooth movement and can be adjusted throughout treatment to achieve desired results.

-

Ligatures:

- Ligatures are used to hold the archwire in place within the bracket slots. They can be elastic or metal, and their selection can affect the friction and force applied to the teeth.

-

Auxiliary Components:

- Additional components such as springs, elastics, and separators may be used to enhance the mechanics of the Edgewise system and facilitate specific tooth movements.

Advantages of the Edgewise Technique

-

Precision:

- The Edgewise Technique allows for precise control of tooth movement in all three dimensions, making it suitable for complex cases.

-

Versatility:

- It can be used to treat a wide range of malocclusions, including crowding, spacing, overbites, underbites, and crossbites.

-

Effective Force Application:

- The design of the brackets and the use of archwires enable the application of light, continuous forces, which are more effective and comfortable for patients.

-

Predictable Outcomes:

- The technique is based on established principles of biomechanics, leading to predictable and consistent treatment outcomes.

Applications of the Edgewise Technique

- Comprehensive Orthodontic Treatment: The Edgewise Technique is commonly used for full orthodontic treatment in both children and adults.

- Complex Malocclusions: It is particularly effective for treating complex cases that require detailed tooth movement and alignment.

- Retention: After active treatment, the Edgewise system can be used in conjunction with retainers to maintain the corrected positions of the teeth.

Forces Required for Tooth Movements

-

Tipping:

- Force Required: 50-75 grams

- Description: Tipping involves the movement of a tooth around its center of resistance, resulting in a change in the angulation of the tooth.

-

Bodily Movement:

- Force Required: 100-150 grams

- Description: Bodily movement refers to the translation of a tooth in its entirety, moving it in a straight line without tipping.

-

Intrusion:

- Force Required: 15-25 grams

- Description: Intrusion is the movement of a tooth into the alveolar bone, effectively reducing its height in the dental arch.

-

Extrusion:

- Force Required: 50-75 grams

- Description: Extrusion involves the movement of a tooth out of the alveolar bone, increasing its height in the dental arch.

-

Torquing:

- Force Required: 50-75 grams

- Description: Torquing refers to the rotational movement of a tooth around its long axis, affecting the angulation of the tooth in the buccolingual direction.

-

Uprighting:

- Force Required: 75-125 grams

- Description: Uprighting is the movement of a tilted tooth back to its proper vertical position.

-

Rotation:

- Force Required: 50-75 grams

- Description: Rotation involves the movement of a tooth around its long axis, changing its orientation within the dental arch.

-

Headgear:

- Force Required: 350-450 grams on each side

- Duration: Minimum of 12-14 hours per day

- Description: Headgear is used to control the growth of the maxilla and to correct dental relationships.

-

Face Mask:

- Force Required: 1 pound (450 grams) per side

- Duration: 12-14 hours per day

- Description: A face mask is used to encourage forward growth of the maxilla in cases of Class III malocclusion.

-

Chin Cup:

- Initial Force Required: 150-300 grams per side

- Subsequent Force Required: 450-700 grams per side (after two months)

- Duration: 12-14 hours per day

- Description: A chin cup is used to control the growth of the mandible and improve facial aesthetics.

Anchorage in orthodontics refers to the resistance that the anchorage area offers to unwanted tooth movements during orthodontic treatment. Proper understanding and application of anchorage principles are crucial for achieving desired tooth movements while minimizing undesirable effects on adjacent teeth.

Classification of Anchorage

1. According to Manner of Force Application

-

Simple Anchorage:

- Achieved by engaging a greater number of teeth than those being moved within the same dental arch.

- The combined root surface area of the anchorage unit must be at least double that of the teeth to be moved.

-

Stationary Anchorage:

- Defined as dental anchorage where the application of force tends to displace the anchorage unit bodily in the direction of the force.

- Provides greater resistance compared to anchorage that only resists tipping forces.

-

Reciprocal Anchorage:

- Refers to the resistance offered by two malposed units when equal and opposite forces are applied, moving each unit towards a more normal occlusion.

- Examples:

- Closure of a midline diastema by moving the two central incisors towards each other.

- Use of crossbite elastics and dental arch expansions.

2. According to Jaws Involved

- Intra-maxillary Anchorage:

- All units offering resistance are situated within the same jaw.

- Intermaxillary Anchorage:

- Resistance units in one jaw are used to effect tooth movement in the opposing jaw.

- Also known as Baker's anchorage.

- Examples:

- Class II elastic traction.

- Class III elastic traction.

3. According to Site

-

Intraoral Anchorage:

- Both the teeth to be moved and the anchorage areas are located within the oral cavity.

- Anatomic units include teeth, palate, and lingual alveolar bone of the mandible.

-

Extraoral Anchorage:

- Resistance units are situated outside the oral cavity.

- Anatomic units include the occiput, back of the neck, cranium, and face.

- Examples:

- Headgear.

- Facemask.

-

Muscular Anchorage:

- Utilizes forces generated by muscles to aid in tooth movement.

- Example: Lip bumper to distalize molars.

4. According to Number of Anchorage Units

-

Single or Primary Anchorage:

- A single tooth with greater alveolar support is used to move another tooth with lesser support.

-

Compound Anchorage:

- Involves more than one tooth providing resistance to move teeth with lesser support.

-

Multiple or Reinforced Anchorage:

- Utilizes more than one type of resistance unit.

- Examples:

- Extraoral forces to augment anchorage.

- Upper anterior inclined plane.

- Transpalatal arch.

Myofunctional Appliances

- Myofunctional appliances are removable or fixed devices that aim to correct dental and skeletal discrepancies by promoting proper oral and facial muscle function. They are based on the principles of myofunctional therapy, which focuses on the relationship between muscle function and dental alignment.

-

Mechanism of Action:

- These appliances work by encouraging the correct positioning of the tongue, lips, and cheeks, which can help guide the growth of the jaws and the alignment of the teeth. They can also help in retraining oral muscle habits that may contribute to malocclusion, such as thumb sucking or mouth breathing.

Types of Myofunctional Appliances

-

Functional Appliances:

- Bionator: A removable appliance that encourages forward positioning of the mandible and helps in correcting Class II malocclusions.

- Frankel Appliance: A removable appliance that modifies the position of the dental arches and improves facial aesthetics by influencing muscle function.

- Activator: A functional appliance that promotes mandibular growth and corrects dental relationships by positioning the mandible forward.

-

Tongue Retainers:

- Devices designed to maintain the tongue in a specific position, often used to correct tongue thrusting habits that can lead to malocclusion.

-

Mouthguards:

- While primarily used for protection during sports, certain types of mouthguards can also be designed to promote proper tongue posture and prevent harmful oral habits.

-

Myobrace:

- A specific type of myofunctional appliance that is used to correct dental alignment and improve oral function by encouraging proper tongue posture and lip closure.

Indications for Use

- Malocclusions: Myofunctional appliances are often indicated for treating Class II and Class III malocclusions, as well as other dental alignment issues.

- Oral Habits: They can help in correcting harmful oral habits such as thumb sucking, tongue thrusting, and mouth breathing.

- Facial Growth Modification: These appliances can be used to influence the growth of the jaws in growing children, promoting a more favorable dental and facial relationship.

- Improving Oral Function: They can enhance functions such as chewing, swallowing, and speech by promoting proper muscle coordination.

Advantages of Myofunctional Appliances

- Non-Invasive: Myofunctional appliances are generally non-invasive and can be a more comfortable option for patients compared to fixed appliances.

- Promotes Natural Growth: They can guide the natural growth of the jaws and teeth, making them particularly effective in growing children.

- Improves Oral Function: By retraining oral muscle function, these appliances can enhance overall oral health and function.

- Aesthetic Appeal: Many myofunctional appliances are less noticeable than traditional braces, which can be more appealing to patients.

Limitations of Myofunctional Appliances

- Compliance Dependent: The effectiveness of myofunctional appliances relies heavily on patient compliance. Patients must wear the appliance as prescribed for optimal results.

- Limited Scope: While effective for certain types of malocclusions, myofunctional appliances may not be suitable for all cases, particularly those requiring significant tooth movement or surgical intervention.

- Adjustment Period: Patients may experience discomfort or difficulty adjusting to the appliance initially, which can affect compliance.

Growth is the increase in size It may also be defined as the normal change in the amount of living substance. eg. Growth is the quantitative aspect and measures in units of increase per unit of time.

Development

It is the progress towards maturity (Todd). Development may be defined as natural sequential series of events between fertilization of ovum and adult stage.

Maturation

It is a period of stabilization brought by growth and development.

CEPHALOCAUDAL GRADIENT OF GROWTH

This simply means that there is an axis of increased growth extending from the head towards feet. At about 3rd month of intrauterine life the head takes up about 50% of total body length. At this stage cranium is larger relative to face. In contrast the limbs are underdeveloped.

By the time of birth limbs and trunk have grown faster than head and the entire proportion of the body to the head has increased. These processes of growth continue till adult.

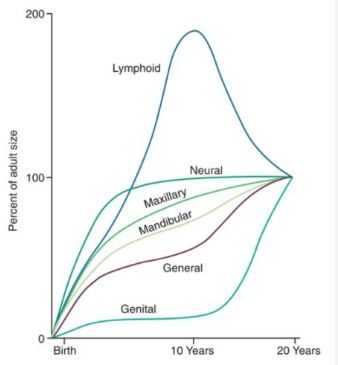

SCAMMON’S CURVE

In normal growth pattern all the tissue system of the body do not growth at the same rate. Scammon’s curve for growth shows 4 major tissue system of the body;

• Neural

• Lymphoid

• General: Bone, viscera, muscle.

• Genital

The graph indicates the growth of the neural tissue is complete by 6-7 year of age. General body tissue show an “S” shaped curve with showing of rate during childhood and acceleration at puberty. Lymphoid tissues proliferate to its maximum in late childhood and undergo involution. At the same time growth of the genital tissue accelerate rapidly.

Frankel appliance is a functional orthodontic device designed to guide facial growth and correct malocclusions. There are four main types: Frankel I (for Class I and Class II Division 1 malocclusions), Frankel II (for Class II Division 2), Frankel III (for Class III malocclusions), and Frankel IV (for specific cases requiring unique adjustments). Each type addresses different dental and skeletal relationships.

The Frankel appliance is a removable orthodontic device that plays a crucial role in the treatment of various malocclusions. It is designed to influence the growth of the jaw and dental arches by modifying muscle function and promoting proper alignment of teeth.

Types of Frankel Appliances

-

Frankel I:

- Indications: Primarily used for Class I and Class II Division 1 malocclusions.

- Function: Helps in correcting overjet and improving dental alignment.

-

Frankel II:

- Indications: Specifically designed for Class II Division 2 malocclusions.

- Function: Aims to reposition the maxilla and improve the relationship between the upper and lower teeth.

-

Frankel III:

- Indications: Used for Class III malocclusions.

- Function: Encourages forward positioning of the maxilla and helps in correcting the skeletal relationship.

-

Frankel IV:

- Indications: Suitable for open bites and bimaxillary protrusions.

- Function: Focuses on creating space and improving the occlusion by addressing specific dental and skeletal issues.

Key Features of Frankel Appliances

-

Myofunctional Design: The appliance is designed to utilize the forces generated by muscle function to guide the growth of the dental arches.

-

Removable: Patients can take the appliance out for cleaning and during meals, which enhances comfort and hygiene.

-

Custom Fit: Each appliance is tailored to the individual patient's dental anatomy, ensuring effective treatment.

Treatment Goals

-

Facial Balance: The primary goal of using a Frankel appliance is to achieve facial harmony and balance by correcting malocclusions.

-

Functional Improvement: It promotes the establishment of normal muscle function, which is essential for long-term dental health.

-

Arch Development: The appliance aids in the development of the dental arches, providing adequate space for the eruption of permanent teeth.